Unlocking Difference of Two Squares

Planned and purposeful journey of multiplication: building on the area model to unlock quadratic free difference of two squares.

We're always striving to make mathematical concepts click for our students, aren't we? We've spent the last three years really digging deep into our models, methods, and pedagogy here at our school, all with the aim of making the curriculum as accessible and rewarding as possible. As I've written about before, we've been developing this powerful approach to build conceptual understanding. And I'm thrilled to share a breakthrough we've had with a particularly tricky topic: the difference between two squares.

We follow the Complete Maths staged curriculum, in which in Stage 8, students are introduced to factorising into the difference of two squares. For context, at this point, our students had already mastered expanding single brackets and were moving onto factorising them. However, crucially, they hadn't yet been formally taught to expand pairs of binomials or factorise into two binomials.

For two years, we were stumped. How on earth do you effectively integrate the difference of two squares when the foundational knowledge of expanding and factorising quadratics isn't explicitly there yet?

The Area Model Breakthrough

This year, everything clicked. After a consistent and sustained embedding of the area model, and with brilliant insights from an in-person CPD session organised in partnership with Complete Maths, I finally cracked it. We've managed to implement the difference of two squares effectively into our curriculum. How? By applying our planned and purposeful journey of multiplication using the area model.

Missing Digits and Zero Pairs within the Area Model

The approach gained traction by giving my students missing digit problems. These seemingly simple problems, when carefully crafted, naturally led them towards the concept of the difference of two squares. We started numerically, then transitioned to algebra. These problems encouraged students to combine multiplication, division, and finding the highest common factors within the model. All of which support factorisation.

Let’s start by using a numerical example:

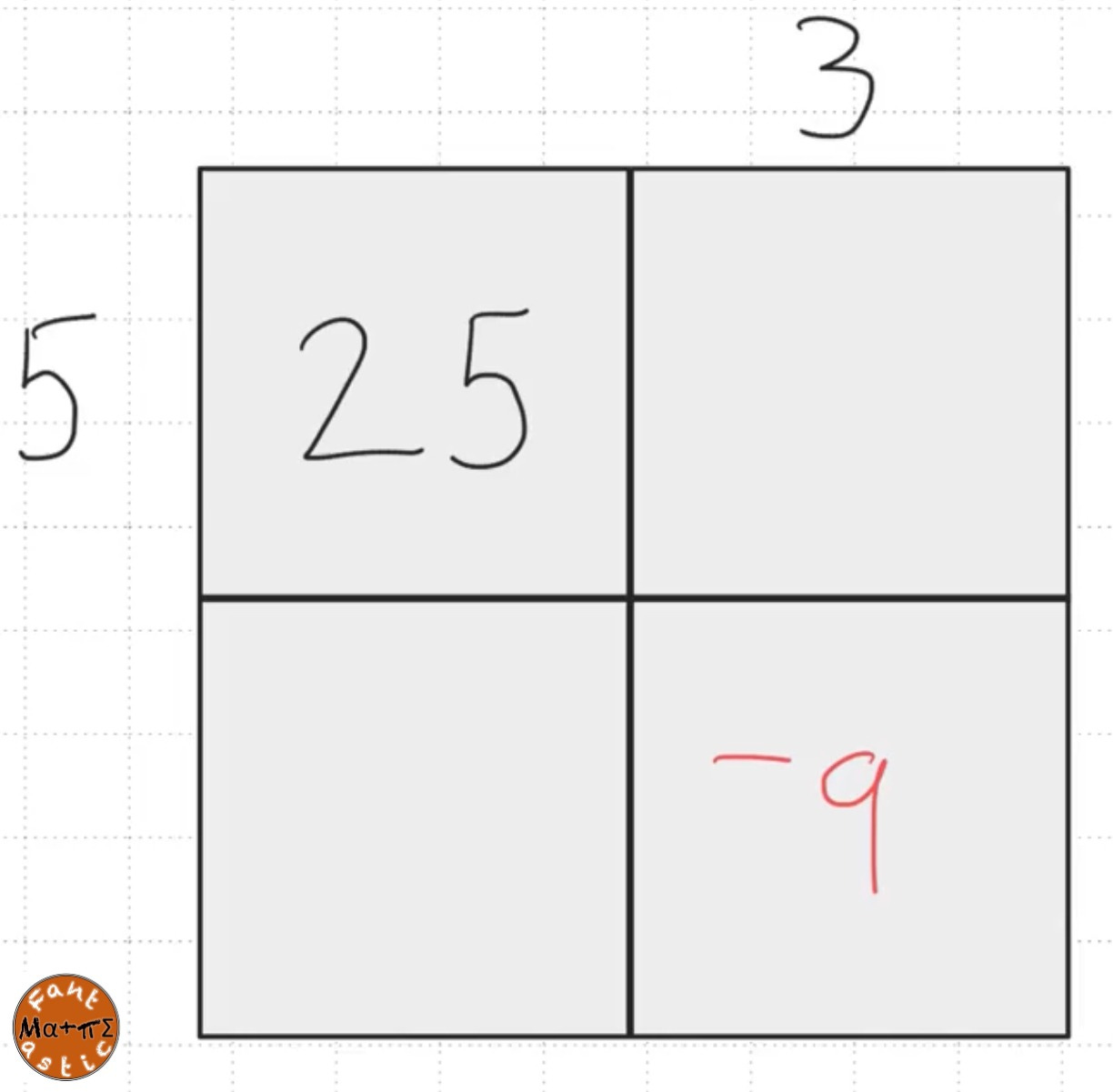

Imagine asking students to fill in the blanks using the area model, let’s consider the model below.

In this example we have the squares with a missing side given. Students completed this on whiteboards with no instruction. But lots of my classes are used to, give it a go see how far you can get. This helps me to assess where my explanation needs to start.

I’m checking do they understand that 5 x ___ = 25 needs to be a 5. After that I’m checking do they know they need to multiply negative 3 by 3 to give negative 9.

Have they multiplied out the rest of the area model correctly? If they have, then I am drawing attention to the zeros pairs on the diagonal.

Let's look at how this might look in practise:

As we’ve said we are going to draw their attention to the 15 and -15 terms are zero pairs. We are going to highlight that we started with 25 - 9.

Notice, there are no written instructions here. Just the model, their own familiarity with how the model works.

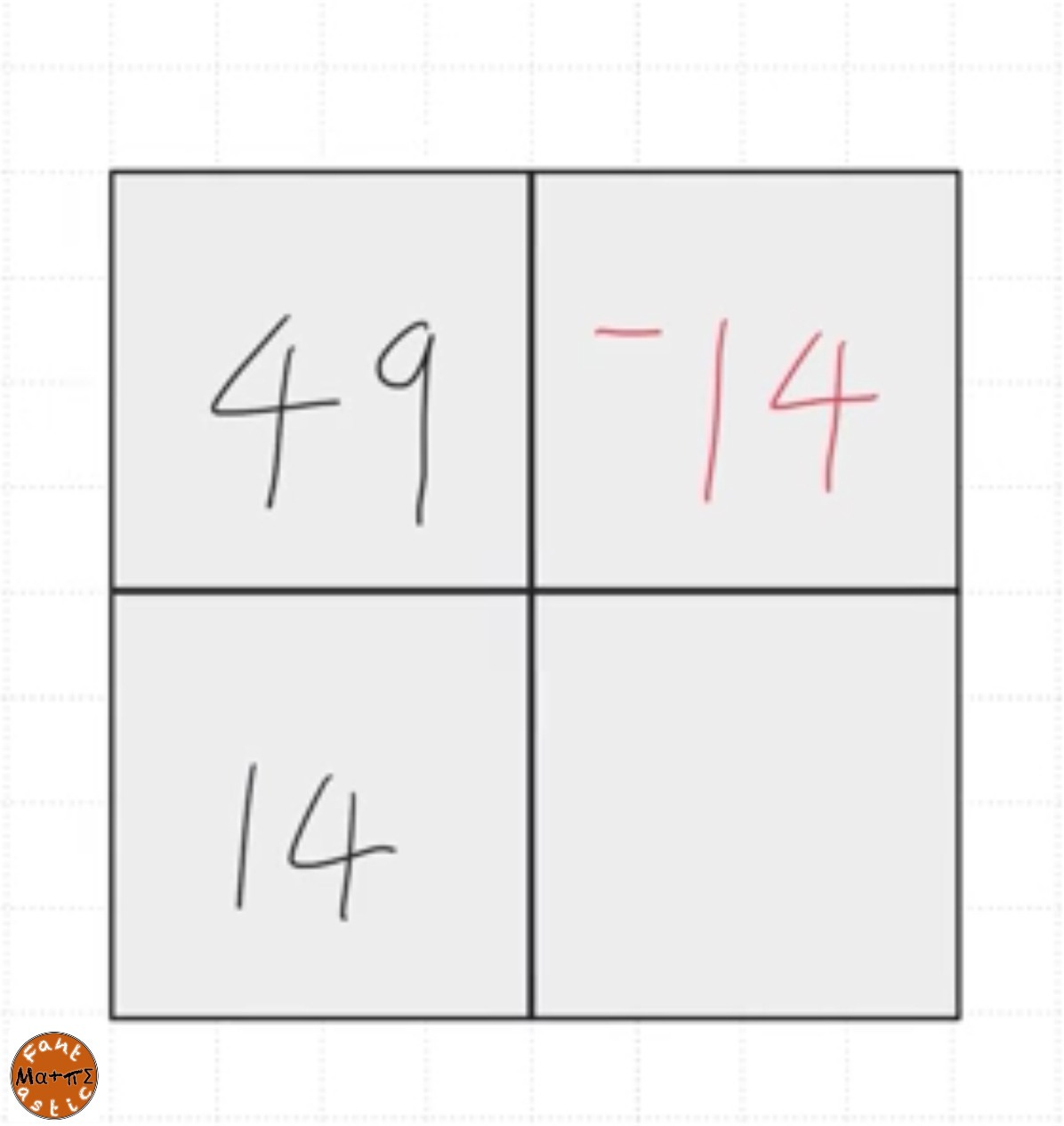

Once I was happy they understood the model in this form, I changed the location of the numbers, exploring:

Now we had common factors to consider, students again were asked to try themselves. But I was highlighting the use of highest common factor afterwards.

This time we started with the zero pairs 14 and -14 which helps us to draw attention to the leaving 49 and negative 4 at the end.

After this we moved into the algebraic where the top left square was usually 𝑥 squared. At this point, the numeric had secured the understanding by working with familiar numbers, so the algebraic presents the generalisation and little structural difference. This numeric to algebraic is a theme that helps my students move from the familiar to the unfamiliar.

It might also be worth nothing that I would have included expanding difference of two squares as part of teaching students different partitioning approaches when multiplying two near squares. This way I have foreshadowed the work.

Incidental Factorisation, Purposeful Learning

So, what had they just done? The students had, in essence, factorised a quadratic in the form of the difference of two squares without ever having been explicitly taught to factorise a quadratic. They had also - almost by accident - expanded binomials without formal instruction. They applied their existing knowledge, guided by carefully chosen problems within the area model, to build and develop new understanding. The exploration of how the expansion led to those crucial zero pairs was the real lightbulb moment.

These connections are incredibly powerful. It reminds me of the success we've had with other 'sticky' topics, like how we managed to get our students to grasp polynomial division in just 15 minutes of tuition.

These gains are all part of our planned and purposeful journey of multiplication throughout our curriculum.

By focusing on the underlying structure through the area model and encouraging purposeful exploration using missing digit problems within the area model, we've unlocked a way for our students to truly understand the difference of two squares, building a solid foundation without needing to pre-teach more advanced concepts. It's a testament to the power of a coherent, well-planned curriculum and a deep understanding of pedagogical models.